|

| Borrowed from www.itworld.com |

The Fallacy of Converting Requirements into User Stories

I don't know how many of my Product Management peers (or those others of my friends who work with scrum teams) have experienced a transmogrification/migration of a waterfall/RUP team to agile, but one common element seems to be the initial attempt of moving existing requirements into User Story format. Invariably a list of requirements is simply moved into an agile project with little or no editing - and it's amazing how many shops think that this completes the transfer. I also had a very interesting experience while working with a fledgling team in a new jira implementation which I'd like to relate.

The story of Excess

I had come into a new team that was trying to adopt to a scrum framework. While the product manager had some agile experience, it turned out to be rather sub-optimal to what would be considered a good, best-practices based agile approach (that PdM wasn't me, by the way). The requirements that he had inherited when hired defined a fairly large online application with multiple components include most of those you usually find: user creation, onboarding and maintenance; order lifecycle management; business process management; reporting and analytics, etc. Those requirements had been collected via existing business analysts and put into a traditional requirements document by an outsourced company via a product management requirements application (I don't recall which one, but basically each topic, section, sub-section, use casee, etc cascaded in an orderly fashion using numbering: 1.1.1.1 - you've probably encountered this before).

In a rush to get these into user story format, this PdM had all the data exported from this tool into a flat file (spreadsheet) and then imported into the adopted agile management software (in this case, jira). Since very little manipulation of the data was done before the import, this resulted in line items defining topic headers turning into User Stories with little to no content. I'm talking thousands of user stories with hundreds of summaries and no descriptions. Trying to sort this out, this PdM then had the company license a plug-in called "structure" (or something similar) that would then straighten out all the stories into some type of readable hierarchy. The whole process ended up taking several months. At some point I was asked my opinion about the whole thing (or perhaps I saw the result in conversation and just opened my big mouth, I don't recall which) I asked "Why don't you just start with the first component and decompose it into useful stories, describing an MVP to get the project going?" - actually my question wasn't that elegantly phrased, but I want to get this story going). The argument against doing this method was that so much time had already been spent with the current export/import mess. Of course this went on for several months - and the development team wasn't very happy with these stories or the way things were being prioritized. I eventually convinced the PdM to try my way and junked all those existing stories into an unused project.

So what went wrong, exactly?

- The product manager was pushed into doing something with the existing requirements so the project could get moving. For the sake of speed and being able to claim "There's 2000 user stories in the backlog" the export/import wasn't thought out very well. At minimum, when you use this type of approach, you should consider how the data is formatted (perhaps by doing a few sample records and seeing how things go?) and making adjustments on either side of the ETL or via a manual clean-up of the data file. To me pulling in requirements like this is probably a good way to have starting, stubbed-in topics but lack just about everything else necessary for a good agile backlog of user stories.

- Trying to fix this kind of mess causes it's own time-suck - months were used in trying to first interpret the lack of canonical structure, then by selecting software that made an agile tool more like a traditional waterfall requirements tool, the stories themselves gained very little (it ended up just making things easier to read for the PdM, otherwise there was little to gain). Months ended up being used to fit all the user stories into the hierarchy that the structured tool provided. That time would have been better spent establishing a method of establishing MVP for each project phase and working with the scrum team to determine the best approach (this last bit was made difficult as the team was still being hired - the product manager did the best he could with what he had).

- The third factor had more to do with time pressure and the need to derive some value from the work that had already been done. I'll focus on that a bit in the next section as a potential process solution.

So what is a better way?

It's always easier to look back and figure out what went wrong and fortunately we all survive to learn from mistakes. I'm going to cheat a bit and limit the solution to converting existing documentation rather than go all high-and-mighty about how the requirements were derived. We who have been practicing agile and scrum for a long time realize that there are many approaches to translating requirements into user stories and much depends on the expectations of the team, company and established principles. Some methods are good, some not so good, and sometimes we have little choice in the matter. For me, I like to have conversations with the people using the software (the business, consumer or end-user) and work backwards towards the solution, focusing on the desired outcome rather than on the tactical implementation - that latter part I think ideally should be determined by the entire team. Unfortunately in shops that are adopting agile, there's a lot of baggage that we all have to contend with and sometimes it's just not worth the effort to overhaul the entire process - better to make small improvements that lead to big changes over time. So how would I approach a similar scenario as my story above?

- First I would carefully read and try to understand the existing documentation. Presumably it's been done well and is worth circulating to engineering and executive leadership - after all someone had to go to the effort of putting it together. I would also do some spot checking against any critical requirements to ensure that enough due diligence was done while putting the document together, by validating those assumptions with end-users.

- Next, I would circulate the overall effort with engineering leadership to help define the near and future goals of the software. This is to establish some design principles and at least create a contextual framework focused on data, objects, interfaces and general principles, especially around the moving, calling and updating of data. Your engineers usually already have some coding standards - now is the time to get buy-in from the group so there's a bit of consistency in implementation against the overall project scope. The outcome of this should be some good architectural diagrams of the various components necessary to get to the endgame. This can then suggest the best method of execution and the start of user story creation.

- Using the existing document, I would then see if the topic headers fit the suggested method of execution - the higher-level topics become epics that are further decomposed into user stories. Sometimes the sub-topics fit well, and other times they don't so they may not be very helpful (generally they are).

- The guts of the requirements are then used to write the user stories, which should be abstracted. Typical requirements are too specific - they tell the user what to do. Instead the approach should be one that tells the developer what the end-user want's to accomplish as a foundation of a collaborative user story. The baseline requirements could still be useful in determining the number of field values that may be required due to some external dependencies, etc but in general the perspective of the story itself should focus on who has a need rather than what needs to be done.

- At this point the high-level topics for the near-term should be fairly well defined, with less definition for the other parts of the project. As each component part is elevated in priority in the backlog, each story is evaluated by the entire scrum team with a focus on context and what the feature is trying to solve. The story is edited to make sure that we're all on the same page and there's a clearly defined acceptance criteria so we all know whether the story has been successfully completed.

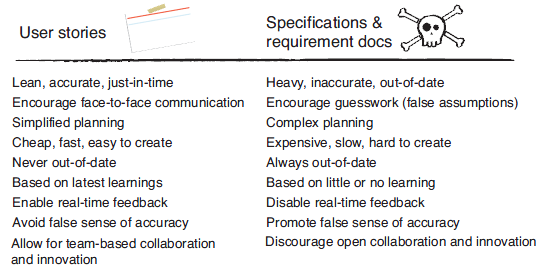

So easy, right? Like I wrote earlier, its much easier to determine what went wrong and suggest something better in retrospect, rather than while things are happening. The fallacy that I refer to in the title is the assumption that a Requirement from traditional waterfall or RUP development means the same thing as a User Story in Agile/scrum. They simply don't, and because the intent of each is different, relabeling doesn't work.

|

| Borrowed from http://agile4freshmen.blogspot.com/ |

I remember my first experience with agile - we did exactly the wrong thing. I basically took a traditional requirements document and did a search-and-replace of "Requirement" to "User Story" - see, since we were also doing scrums, we're doing agile! It actually took quite a bit of time and experience to realize that what we were doing was adopting some of the ceremonies and artifacts without really understanding how things fit together. The problem is that often even adopting small parts of the agile framework can produce a positive result where a development team sees improvement. It's my opinion that there are as many teams that think they have successfully adopted agile as there are those where agile adoption has failed, each for the same lack of understanding.

-- John

(also published on LinkedIn)